Esfandiyar's Saga

A Mythical Journey in Music and Words by Arashk Azizi

Esfandiyar’s Saga is a monumental, multi-disciplinary project by Arashk Azizi, currently in development — a mythopoetic exploration of one of the most complex heroes of Persian mythology. Rooted in the ancient texts of the Shahnameh, Bahman Nameh, and the Avesta, this project reimagines the life of Esfandiyar, not just as a tragic prince and warrior, but as a deeply human figure torn between duty, divinity, and destiny.

Spanning three major musical compositions and a full-length literary work, the project unfolds in four major parts — each illuminating a different phase of Esfandiyar’s life and inner journey.

The Book: Esfandiyar’s Saga

At the heart of this project lies a written narrative titled Esfandiyar’s Saga — a contemporary reimagining of the legendary prince’s life, drawing on ancient sources while offering new philosophical depth. While many know Esfandiyar as the invincible warrior tragically killed by Rostam, this book portrays him as a man of conscience, entangled in divine expectations and royal manipulation. Inspired by the storytelling style of Ferdowsi and the introspective themes of modern literature, Arashk's book combines elements of epic poetry, prose fiction, and allegory.

Key sources include:

The Shahnameh by Ferdowsi – the primary narrative source for Esfandiyar’s battles and fate.

Bahman Nameh – extending the story into the legacy of his son and the implications of Esfandiyar’s death.

The Avesta – particularly the spiritual dimensions of Esfand and the connection to Sepandarmazd, one of the Amesha Spentas, which redefines Esfandiyar’s symbolic role in this work.

I. Sonata: “Esfandiyar Sonata”

Arashk Azizi in this piano sonata, explores Esfandiyar’s early life, including:

His baptism by Zoroaster, making him invulnerable to harm — except for his eyes, left untouched to symbolize vision, vulnerability, and inner truth.

His youth and moral awakening, shaped by spiritual guidance rather than warfare.

His first acts of duty in the fight against the invading Arjasb, setting the foundation for the conflict between inner nobility and external expectations.

This work is structured in three movements:

Zarathustra's Gift – Mystical, reverent textures reflect Esfandiyar’s divine origins.

The Herald – A thematic shift into tension and urgency while keepin a positive mood, as he enters political and military conflict.

Esfandiyar in Chains – A brooding, emotionally turbulent finale exploring his betrayal and imprisonment by his own father.

II. Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 9: “Esfandiyar”

This full-scale symphony narrates the iconic seven labors (Haft Khan) — not merely as heroic conquests, but as symbolic trials of character. Each labor becomes a metaphor for inner conflict, existential struggle, and sacrifice. The work culminates in the moment of tragic irony: having survived all divine tests, Esfandiyar is sent to die in a battle engineered by fate and political manipulation.

The Movements which are based on the Esfandiyar's seven labor story from Shahnameh by Ferdowsi, are as follows:

The Wolves

The Lions

The Dragon

The Witch

Simurgh

Ahriman

The Castle

The symphony reframes the traditional notion of victory. It asks: what is the cost of obedience when moral clarity is lost?

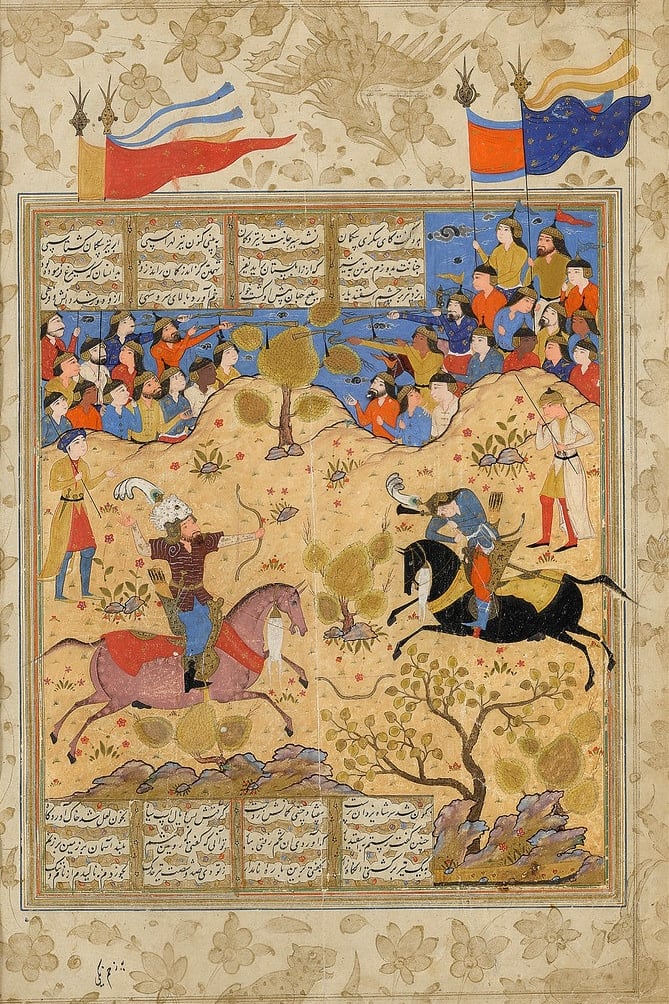

The Seven Labors of Esfandiyar as a symphony

The Seven Labors of Esfandiyar is one of the central episodes in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (The Book of Kings), recounting the perilous journey of the invincible prince Esfandiyar as he sets out to rescue his sisters from Arjasb, the King of Turan. In this mythic tale, the hero must endure and overcome seven formidable trials before reaching Arjasb’s stronghold, where his sisters are held captive. Each labor tests not only his physical strength but also his resilience, wisdom, and endurance.

In Arashk Azizi’s symphonic retelling, the emphasis shifts from purely physical heroism to the inner battles that define the man behind the legend. While the original story celebrates Esfandiyar’s courage and divine protection, this symphony focuses on his internal struggles — the doubts, the temptations, and the moments of spiritual collapse that accompany the journey.

The central motif of the work — a simple, ascending melodic line resting on the primary chords of the scale — represents the purity and moral clarity of Esfandiyar’s character. Yet, as the journey unfolds, this theme is repeatedly distorted, broken, and reshaped in encounters with the antagonists he faces. These interruptions in the melody serve as musical metaphors for the corruption and hardship that threaten to erode the hero’s integrity.

Structure of the Esfandiyar Symphony

The work is conceived in three overarching sections:

Movements I–V: The Tangible Struggles

The first five movements correspond to the initial labors, where the dangers are more tangible and external: monstrous beasts, hostile lands, and treacherous paths. The music carries an epic tone — sweeping orchestral gestures, rhythmic drive, and martial energy dominate. Yet, when these movements are experienced back-to-back, subtle harmonic shifts and thematic callbacks reveal a deeper undercurrent: these are not isolated battles but stages in an unfolding psychological journey.Movement VI: The Battle with Ahriman

In the Shahnameh, this is the confrontation with the evil, creating a snow storm. In the symphony, however, Ahriman’s presence is internalized — the battle takes place not on a battlefield but within Esfandiyar’s own spirit. Here, the once-steadfast theme of the hero crumbles under its own weight, collapsing into fragmented motifs. The turning point comes when, from the depths of musical disintegration, the theme rises again — transformed, strengthened — leading to a climactic victory. This is less a conquest over an enemy than a reclamation of self. This is a definitive moment not only in this symphony, but throughout the whole Esfandiyar's saga.Movement VII: Apotheosis

The final movement represents the full growth of Esfandiyar as a hero purified by struggle. Having overcome the shadow within, he reflects upon his journey. The music recalls fragments from earlier movements, now reframed in a warm, radiant orchestration. The final section, soaring yet deeply human, brings the symphony to a close — not with triumphant conquest alone, but with a sense of readiness. The hero has completed this chapter of his saga and now stands prepared for the next, fateful stage of his life.

The Original "Haft Khan" Story from the Shahnameh

In Ferdowsi’s epic, the Seven Labors (Haft Khan) begin when King Goshtasp sends his son Esfandiyar on a mission to rescue his sisters, captured by Arjasb, ruler of Turan. Esfandiyar, blessed with invulnerability to all weapons, sets out with a small band of warriors. Along the way, he faces seven great challenges:

The Wolf – Esfandiyar defeats two ferocious wolves that attacks by night.

The Lion – He slays two mighty lions that ambushes his caravan.

The Dragon – Using courage and cunning, he slays a monstrous dragon.

The Witch – He resists the enchantments of a temptress-witch who tries to seduce and destroy him.

The Simurgh – Esfandiyar faces the mighty Simurgh and in an epic fight–similar to the dragon–he slays the Simurgh.

The Frost and Snow – He survives a deadly winter storm created by the devil that threatens to freeze his entire company.

The Defeat of Arjasb – In the final labor, Esfandiyar storms Arjasb’s fortress, defeats the king, and frees his sisters.

In Ferdowsi’s telling, Esfandiyar emerges from these trials undefeated, fulfilling his mission and returning home in glory — only to find himself ensnared in further political and familial strife. The labors, while grand and heroic, are only one stage in the larger tragedy of his life, culminating in his fatal confrontation with Rostam.

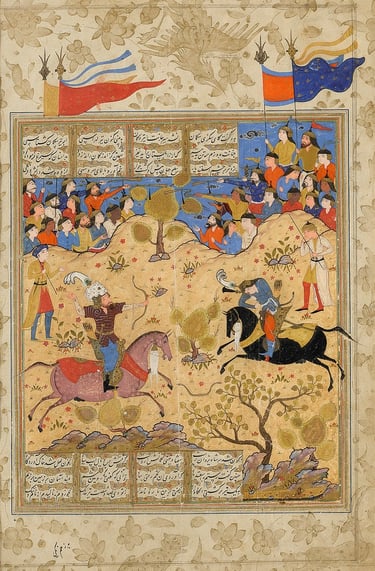

III. Piano Concerto: “Rostam va Esfandiyar”

This piano concerto dramatizes the fateful duel between Esfandiyar and Rostam — two heroes from different generations, clashing not only with weapons but with ideals. In this musical retelling of the famous Rostam o Esfandiyar by Arashk Azizi, the piano represents Esfandiyar — articulate, complex, sometimes restrained — while the orchestra embodies Rostam — raw, ancient, and powerful. The resulting conflict is devastating, with the music descending into an elegy that mourns not just a life lost, but a vision of integrity crushed by power struggles.

Themes and Philosophy

The entire Esfandiyar’s Saga centers on a deeper philosophical contrast:

Obedience vs. Conscience

Mythic Strength vs. Human Fragility

Martyrdom vs. Moral Action

While many traditional heroes seek to uphold the established order, Esfandiyar emerges as a unique figure — one who sees through the manipulation of power, yet still walks toward his fate with quiet strength and integrity. He becomes a symbol of moral courage rather than blind heroism.

In Arashk Azizi's retelling, Esfandiyar is not merely the child of a king, but the spiritual child of arte (goodness) — a man shaped by truth, forced into warfare, and ultimately remembered not for his invulnerability, but for his inner vision.

Esfandiyar, A Hero of Conscience

Throughout world mythology, the archetype of the hero often follows a familiar path: a figure of extraordinary strength who restores the order of the world. Whether it is Rostam in the Shahnameh, Achilles in Greek legend, Rama in Indian epics, or even modern superheroes like Batman, these heroes define themselves by fulfilling the will of a king, a god, or a system. They restore “order” — but this order is often the one sanctioned by power, by the ruling authority, by the structure that already exists.

Esfandiyar stands apart.

In the Shahnameh, he is sent on impossible missions by his father, King Goshtasp — missions that are not born of pure justice, but of political manipulation and personal ambition. Esfandiyar knows this. He is not naïve. He is aware of the underlying motives behind his orders, yet he accepts them, not because he believes in their righteousness, but because he accepts his fate with dignity.

This quiet awareness transforms him into something rare in the world of heroes: a man who fulfills his duty without losing sight of its moral cost. He is obedient, but not blind. He acts, but without illusions. He is both the champion of Iran and a witness to the flawed system he serves.

Here lies his moral complexity. While other heroes fight with the certainty of righteousness, Esfandiyar fights with the knowledge that his actions are shaped by a flawed human world. And yet, he does not retreat into passivity.

There is also a personal, literary parallel I see between prince Esfandiyar and Prince Myshkin from Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. Myshkin is a man of pure heart and moral clarity, yet constantly out of step with the corrupt and cynical world around him. His goodness is not strategic — it is his nature — and in the end, it leads him into suffering. Esfandiyar shares this quiet nobility. Like Myshkin, he moves through a flawed world without allowing it to define him. But unlike Myshkin, Esfandiyar does not remain passive; he engages with his fate, takes up arms when duty demands it, and accepts the tragic cost. In both figures, we see the struggle of moral purity in a world that rewards power over virtue — and in both, there is the haunting question of whether integrity can survive the weight of destiny.

In this way, he differs sharply from Siyavash. Siyavash, another tragic prince of the Shahnameh, is the embodiment of purity and peace. But when faced with injustice, Siyavash withdraws, choosing exile over confrontation, and is ultimately murdered in a foreign land — a martyr to goodness, but a passive one. Esfandiyar, on the other hand, does not run. He steps into the arena, makes mistakes, takes action, and faces conflict head-on. Both men die tragically, but their deaths are of different natures: Siyavash’s is the quiet tragedy of innocence destroyed; Esfandiyar’s is the epic tragedy of a man who chose to fight, even knowing the outcome. For me Siyavash is the face of a saint, a martyr, but Esfandiyar is the face of a human who tries to be good.

This choice — to act consciously in the face of manipulation — makes Esfandiyar an enduring moral figure. His strength is not only in his invulnerability, but in his moral resilience. In the battle with Rostam, his final act is not simply a heroic clash; it is the culmination of a lifetime of walking the fine line between conscience and obedience.

In today’s world, where nations often follow the “classical hero” model of politics — striving to impose their will on others — Esfandiyar suggests another path: to remain strong, but not to lose moral vision. To accept the burdens of fate, but to carry them with integrity. He may not offer a perfect alternative to the politics of power, but he hints at a nobler way of being powerful: power with awareness.

Esfandiyar reminds us that the truest victory may not be in conquering others, but in preserving one’s conscience while walking through the fire of duty.

Status

The Sonata is currently in the final stages of composition. The Symphony has been composed and recorded, it is already available on streaming platforms. The Piano Concerto is conceptually outlined. The book is being written in parallel, drawing connections between mythology, Iranian history, and contemporary relevance.